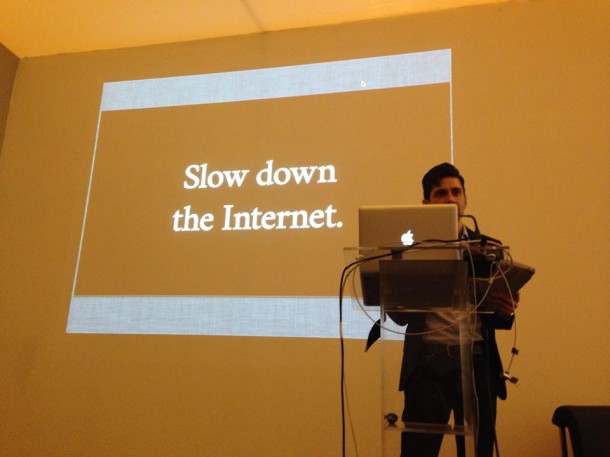

Peter J.Russo at ARCO(e)ditorial presentation.

Peter J.Russo at ARCO(e)ditorial presentation.The biggest problem in art criticism today is the lack of actual criticism. Interview with Peter J Russo

Peter J. Russo is director of Triple Canopy. From 2009 until 2012 he organized Printed Matter’s NY Art Book Fair at MoMA PS1. Triple Canopy is a magazine based in New York that encompasses digital works of art and literature, public conversations, exhibitions, and books. This model hinges on the development of publishing systems that incorporate networked forms of production and circulation. Working closely with artists, writers, technologists, and designers, Triple Canopy produces projects that demand considered reading and viewing.

Rosa Lleó: Triple Canopy is an online magazine that is not as well-known in Europe as it is in the USA, so perhaps you could you tell us, from your personal point of view, about its beginning, how and why it was created and what was its aspiration?

Peter J. Russo: Before becoming interested in contemporary art, I ran a record label called Livewire with some friends. We released recordings of our friends’ bands, published zines, and printed what now seems like thousands of t-shirts. That experience encouraged me to think critically about how culture circulates and is distributed to a broader audience, particularly work that is often considered obscure or difficult to understand. Around 2008, a group of friends began hosting meetings with the aim of founding a magazine. We weren’t sure if the magazine would be published online, as a PDF, or in print after all. Ultimately, it seemed that the Internet was the challenge at hand—to rethink our encounters with art and literature on the Web, which at that point felt fairly impoverished or relegated to a niche interest in exploiting the Internet’s glitches, in the case of Net Art. At the same time, we were thinking about the history of ”new media” publications—in particular Aspen, which had been reconfigured for presentation online by UbuWeb, a useful model for us.

Triple Canopy currently exists as twenty or so editors, designers, and technologists. Everyone brings his or her area of interest to bear on our projects. At least three editors will jointly develop a project with any one contributing artist or writer. Often these collaborative engagements last up to a year or longer and entail a great deal of research. It’s the kind of engagement that’s all too uncommon at small-scale publications and institutions, some of which are in the habit of simply handing over a physical or virtual space to the artist, underestimating the influence or potential longevity of their programs, in my opinion. We know now that’s not enough—the barrier to exposure or visibility seems less daunting, what with all the options artists now have. How an institution or a publication behaves and the public that develops around its work—personally, these seem like more interesting questions to ask.

RL: When you Google Triple Canopy the first thing that appears is a defense contractor…could you tell us more about the decision to choose this name?

PJR: I think our creative director Caleb Waldorf originally suggested it. Triple Canopy has two meanings: Triple Canopy is a private security company that took over the Blackwater contracts under the Bush administration, following the invasion of Iraq. The company’s founders met while on duty in a triple canopy jungle, the densest kind of rainforest. In some sense, we’re reclaiming something beautiful that was made very ugly. Then, of course, the “mercenary” angle is something else. I’ll leave it at that.

RL: You published an interview with Matthew Higgs in which you comment on how normally the first encounter that most of us have with contemporary art is through the book, but somehow this encounter seems understated when compared with our encounter of works in the exhibition space.

PJR: This is the main challenge facing any one with a creative practice today: How can concepts, and not just a representation of those concepts, be made more legible on the Web. I’m talking about the quality of an encounter, not the mere dispersal of an image.

RL: The Aspen boxes are on display at MACBA in Barcelona with small cabinets to listen to the audio and video file, but the majority of texts require a careful reading, which cannot be achieved successfully on an exhibition space…

PJR: Triple Canopy publishes interactive artwork, poetry, fiction, prose, multimedia essays, and other hybrid forms which currently lack a name (suggestions welcome). Many publications do. However, my point is that museum visitors often see new artistic practices shoehorned into the gallery space—computer screens, reading rooms, endless rows of vitrines, etcetera. Triple Canopy in some ways is an attempt to rethink these common practices while paying particular attention to artwork that exceeds the space of the gallery, whether serial or archival in nature, as well as literary engagements that expand beyond the page. Triple Canopy’s exhibition projects don’t merely consist of placing books into the exhibition space but wholly rethinking our encounters with objects as “texts” to be read in relation to one another and interacted with. The social component of each project is very deliberate and thoroughly considered, as was the case with Speculations, our recent project at MoMA PS1 with artist José León Cerrillo plus an invited rosters of over fifty lecturers describing a future they’d like to see.

This month, Triple Canopy will present Pointing Machines, its contribution to the 2014 Whitney Biennial, which consists of a gallery installation and several public programs, including lectures, performances, and tours with outside curators, as well as a catalogue essay. Pointing Machinesexamines the way in which art objects are commissioned, made, collected, disowned, replicated, photographed, exhibited, published, and so forth. Its object of study, if you will, is the famed folk art and furniture collection once belonging to Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, major portions of which were acquired by the NGA, the Met and the Whitney, which later deacessioned its holdings. Interestingly, all three institutions play a major role in the project: the Met, via its loan of a 18th century basin stand once belonging to the Garbisches, of which their grandson Frank Rhodes made a handcrafted replica to be installed alongside a 3D-printed version of the same piece; the NGA, via its loan of a remarkable canvas, “We Go for the Union.” The installation also incorporates original photography, a sound piece made in collaboration with C. Spencer Yeh, archival documents (originally from Sotheby’s, which organized the 1980 and 1999 Garbisch collection auctions), and 8×10 photographs of the Garbisch collection from the Baltimore Sun newspaper. During the coming year, you’ll see these projects and live events rematerialize online as documentation but also as wholly reconceived digital works for Triple Canopy’s platform alongside newly commissioned artwork and writing.

RL: Similar to what happens with art criticism, that it seems to be repeating unsuccessfully the same forms since the last fifty years.

PJR: The biggest problem in art criticism today is the lack of actual criticism. Generally, there is a lack of formal exploration. How can writers venture beyond the 500-word descriptive review into more interesting, more literary territory. How can other media be deployed to critique a work of art? Can you, for instance, critique an exhibition through a juxtaposition of videos and images. There’s a lot of room to explore what are otherwise fairly common curatorial strategies which simply haven’t been widely adopted on the Web. Art criticism, which is to say writing about art, isn’t Triple Canopy’s stated mission but I certainly look forward to seeing how other digital platforms evolve new models.